Docker run command

The basic syntax for the Docker run command looks like this:

k@laptop:~$ docker run --help

Usage: docker run [OPTIONS] IMAGE [COMMAND] [ARG...]

Run a command in a new container

We’re going to use very tiny linux distribution called busybox which has several stripped-down Unix tools in a single executable file and runs in a variety of POSIX environments such as Linux, Android, FreeBSD, etc. It’s going to execute a shell command in a newly created container, then it will put us on a shell prompt:

k@laptop:~$ docker run -it busybox sh

/ # echo 'bogotobogo'

bogotobogo

/ # exit

k@laptop:~$

The docker ps shows us containers:

k@laptop:~$ docker ps

CONTAINER ID IMAGE COMMAND CREATED STATUS PORTS NAMES

But right now, we don’t have any containers running. If we use docker ps -a, it will display all containers even if it’s not running:

k@laptop:~$ docker ps -a

CONTAINER ID IMAGE COMMAND CREATED STATUS PORTS NAMES

4d673944ec59 busybox:latest "sh" 13 minutes ago Exited (0) 12 minutes ago trusting_mccarthy

When we execute run command, it will create a new container and execute a command within that container. The container will remain until it is explicitly deleted. We can restart the container:

k@laptop:~$ docker restart 4d673944ec59

4d673944ec59

We can attach to that container. The usage looks like this:

docker attach [OPTIONS] CONTAINER

Let’s attach to the container. It will put us back on the shell where we were before:

k@laptop:~$ docker attach 4d673944ec59

/ # ls

bin etc lib linuxrc mnt proc run sys usr

dev home lib64 media opt root sbin tmp var

/ # exit

The docker attach command allows us to attach to a running container using the container’s ID or name, either to view its ongoing output or to control it interactively.

Now, we know that a container can be restarted, attached, or even be killed!

k@laptop:~$ docker ps -a

CONTAINER ID IMAGE COMMAND CREATED STATUS PORTS NAMES

4d673944ec59 busybox:latest "sh" 21 minutes ago Exited (0) About a minute ago trusting_mccarthy

But the one thing we can’t do changing the command that’s been executed. So, once we have created a container and it has a command associated with it, that command will always get run when we restart the container. We can restart and attached to it because it has shell command. But if we’re running something else, like an echo command:

k@laptop:~$ docker run -it busybox echo 'bogotobogo'

bogotobogo

Now, we’ve created another container which does echo:

k@laptop:~$ docker ps -a

CONTAINER ID IMAGE COMMAND CREATED STATUS PORTS NAMES

849975841b4e busybox:latest "echo bogotobogo" About a minute ago Exited (0) About a minute ago elegant_goldstine

4d673944ec59 busybox:latest "sh" 29 minutes ago Exited (0) 9 minutes ago trusting_mccarthy

It executed “echo bogotobogo”, and then exited. But it still hanging around. Even if we restart it:

k@laptop:~$ docker restart 849975841b4e

849975841b4e

It run in background and we don’t see any output. All it did “echo bogotobogo” again. I can remove this container:

k@laptop:~$ docker rm 849975841b4e

849975841b4e

Now it’s been removed from our list of containers:

k@laptop:~$ docker ps -a

CONTAINER ID IMAGE COMMAND CREATED STATUS PORTS NAMES

4d673944ec59 busybox:latest "sh" 35 minutes ago Exited (0) 14 minutes ago trusting_mccarthy

We want this one to be removed as well:

k@laptop:~$ docker rm 4d673944ec59

4d673944ec59

k@laptop:~$ docker ps -a

CONTAINER ID IMAGE COMMAND CREATED STATUS PORTS NAMES

k@laptop:~$

docker run -it

Let’s look at the -it in docker run -it.

k@laptop:~$ docker run --help

Usage: docker run [OPTIONS] IMAGE [COMMAND] [ARG...]

Run a command in a new container

-i, --interactive=false Keep STDIN open even if not attached

-t, --tty=false Allocate a pseudo-TTY

...

If we run with t:

k@laptop:~$ docker run -i busybox sh

ls

bin

dev

etc

home

lib

lib64

linuxrc

media

mnt

opt

proc

root

run

sbin

sys

tmp

usr

var

cd home

cd /home

ls

default

ftp

exit

k@laptop:~$

It is interactive mode, and we can do whatever we want: “ls”, “cd /home” etc, however, it does not give us console, tty.

If we issue the docker run with just t:

k@laptop:~$ docker run -t busybox sh

/ #

We get a terminal we can work on. But we can’t do anything because it cannot get any input from us. We can execute anything since it’s not getting what we’re passing in.

k@laptop:~$ docker ps -a

CONTAINER ID IMAGE COMMAND CREATED STATUS PORTS NAMES

3bcaa1d57ac0 busybox:latest "sh" 15 seconds ago Up 14 seconds dreamy_yonath

ac53c2a81ebe busybox:latest "sh" About a minute ago Exited (127) 55 seconds ago condescending_galileo

497be20f5d7e busybox:latest "sh" 3 minutes ago Exited (-1) 2 minutes ago nostalgic_wilson

Docker run –rm

We need to kill the container run with only “t”:

k@laptop:~$ docker kill 3bcaa1d57ac0

3bcaa1d57ac0

k@laptop:~$ docker ps -a

CONTAINER ID IMAGE COMMAND CREATED STATUS PORTS NAMES

3bcaa1d57ac0 busybox:latest "sh" 3 minutes ago Exited (-1) 2 minutes ago dreamy_yonath

ac53c2a81ebe busybox:latest "sh" 3 minutes ago Exited (127) 3 minutes ago condescending_galileo

497be20f5d7e busybox:latest "sh" 6 minutes ago Exited (-1) 4 minutes ago nostalgic_wilson

Then, we want to remove all containers:

k@laptop:~$ docker rm $(docker ps -aq)

3bcaa1d57ac0

ac53c2a81ebe

497be20f5d7e

k@laptop:~$ docker ps -a

CONTAINER ID IMAGE COMMAND CREATED STATUS PORTS NAMES

k@laptop:~$

The argument q in docker ps -aq gives us id of all containers.

The next thing to do here is that we don’t want remove the containers every time we execute a shell command:

k@laptop:~$ docker run -it --rm busybox sh

/ # echo Hello

Hello

/ # exit

k@laptop:~$ docker ps -a

CONTAINER ID IMAGE COMMAND CREATED STATUS PORTS NAMES

k@laptop:~$

Notice that we don’t have any container. By passing in --rm, the container is automatically deleted once the container exited.

k@laptop:~$ docker run -it --rm busybox echo "I will not staying around forever"

I will not staying around forever

k@laptop:~$ docker ps -a

CONTAINER ID IMAGE COMMAND CREATED STATUS PORTS NAMES

k@laptop:~$

Docker rmi – deleting local images

To remove all images from our local machine:

k@laptop:~$ docker rmi $(docker images -q)

Saving container – docker commit

As we work with a container and continue to perform actions on it (install software, configure files etc.), to have it keep its state, we need to commit. Committing makes sure that everything continues from where they left next time.

Exit docker container:

root@f510d7bb05af:/# exit

exit

Then, we can save the image:

# Usage: sudo docker commit [container ID] [image name]

$ sudo docker commit f510d7bb05af my_image

Running CentOS on Ubuntu 14.04

As an exercise, we now want to run CentOS on Ubuntu 14.04.

Before running it, check if we have have any Docker container including running ones:

k@laptop:~$ docker ps

CONTAINER ID IMAGE COMMAND CREATED STATUS PORTS NAMES

OK. There is no running Docker. How about any exited containers:

k@laptop:~$ docker ps -a

CONTAINER ID IMAGE COMMAND CREATED STATUS PORTS NAMES

Nothings there!

Let’s search Docker registry:

k@laptop:~$ docker search centos

NAME DESCRIPTION STARS OFFICIAL AUTOMATED

centos The official build of CentOS. 1223 [OK]

ansible/centos7-ansible Ansible on Centos7 50 [OK]

jdeathe/centos-ssh-apache-php CentOS-6 6.6 x86_64 / Apache / PHP / PHP m... 11 [OK]

blalor/centos Bare-bones base CentOS 6.5 image 9 [OK]

...

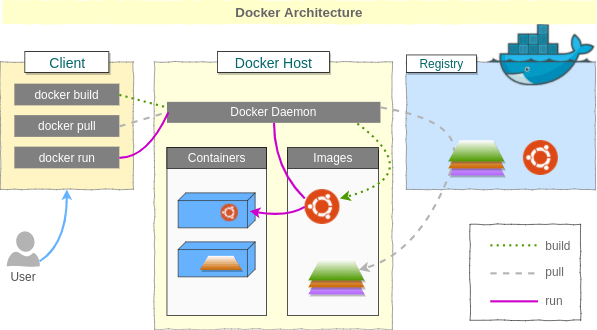

We can download the image using docker pull command. The command find the image by name on Docker Hub and download it from Docker Hub to a local image cache.

k@laptop:~$ docker pull centos

latest: Pulling from centos

c852f6d61e65: Pull complete

7322fbe74aa5: Pull complete

f1b10cd84249: Already exists

Digest: sha256:90305c9112250c7e3746425477f1c4ef112b03b4abe78c612e092037bfecc3b7

Status: Downloaded newer image for centos:latest

Note that when the image is successfully downloaded, we see a 12 character hash: Download complete which is the short form of the image ID. These short image IDs are the first 12 characters of the full image ID – which can be found using docker inspect or docker images –no-trunc=true:

k@laptop:~$ docker inspect centos:latest

[

{

"Id": "7322fbe74aa5632b33a400959867c8ac4290e9c5112877a7754be70cfe5d66e9",

"Parent": "c852f6d61e65cddf1e8af1f6cd7db78543bfb83cdcd36845541cf6d9dfef20a0",

"Comment": "",

"Created": "2015-06-18T17:28:29.311137972Z",

"Container": "d6b8ab6e62ce7fa9516cff5e3c83db40287dc61b5c229e0c190749b1fbaeba3f",

"ContainerConfig": {

"Hostname": "545cb0ebeb25",

"Domainname": "",

"User": "",

"AttachStdin": false,

"AttachStdout": false,

"AttachStderr": false,

"PortSpecs": null,

"ExposedPorts": null,

"Tty": false,

"OpenStdin": false,

"StdinOnce": false,

"Env": null,

"Cmd": [

"/bin/sh",

"-c",

"#(nop) CMD [\"/bin/bash\"]"

],

"Image": "c852f6d61e65cddf1e8af1f6cd7db78543bfb83cdcd36845541cf6d9dfef20a0",

"Volumes": null,

"VolumeDriver": "",

"WorkingDir": "",

"Entrypoint": null,

"NetworkDisabled": false,

"MacAddress": "",

"OnBuild": null,

"Labels": {}

},

"DockerVersion": "1.6.2",

"Author": "The CentOS Project \u003ccloud-ops@centos.org\u003e - ami_creator",

"Config": {

"Hostname": "545cb0ebeb25",

"Domainname": "",

"User": "",

"AttachStdin": false,

"AttachStdout": false,

"AttachStderr": false,

"PortSpecs": null,

"ExposedPorts": null,

"Tty": false,

"OpenStdin": false,

"StdinOnce": false,

"Env": null,

"Cmd": [

"/bin/bash"

],

"Image": "c852f6d61e65cddf1e8af1f6cd7db78543bfb83cdcd36845541cf6d9dfef20a0",

"Volumes": null,

"VolumeDriver": "",

"WorkingDir": "",

"Entrypoint": null,

"NetworkDisabled": false,

"MacAddress": "",

"OnBuild": null,

"Labels": {}

},

"Architecture": "amd64",

"Os": "linux",

"Size": 0,

"VirtualSize": 172237380

}

]

Or:

k@laptop:~$ docker images --no-trunc=true

REPOSITORY TAG IMAGE ID CREATED VIRTUAL SIZE

centos latest 7322fbe74aa5632b33a400959867c8ac4290e9c5112877a7754be70cfe5d66e9 8 weeks ago 172.2 MB

k@laptop:~$ docker images --no-trunc=false

Or:

k@laptop:~$ docker images

REPOSITORY TAG IMAGE ID CREATED VIRTUAL SIZE

centos latest 7322fbe74aa5 8 weeks ago 172.2 MB

Let’s run Docker with the image:

k@laptop:~$ docker run -it centos:latest /bin/bash

[root@33b55acb4814 /]#

Now, we are on CentOS. Let’s make a file, and then just exit:

[root@33b55acb4814 /]# cd /home

[root@33b55acb4814 home]# touch bogo.txt

[root@33b55acb4814 home]# ls

bogo.txt

[root@33b55acb4814 home]# exit

exit

k@laptop:~$

Check if there is any running container:

k@laptop:~$ docker ps

CONTAINER ID IMAGE COMMAND CREATED STATUS PORTS NAMES

Nothings’ there. The docker ps command shows only the running containers. So, if we want to see all containers, we need to add -a flag to the command:

k@laptop:~$ docker ps -a

CONTAINER ID IMAGE COMMAND CREATED STATUS PORTS NAMES

33b55acb4814 centos:latest "/bin/bash" 2 minutes ago Exited (0) 51 seconds ago grave_jang

We do not have any Docker process that’s actively running. But we can restart the one that we’ve just exited from.

$ docker restart 33b55acb4814

33b55acb4814

k@laptop:~$ docker ps

CONTAINER ID IMAGE COMMAND CREATED STATUS PORTS NAMES

33b55acb4814 centos:latest "/bin/bash" 4 minutes ago Up 4 seconds grave_jang

Note that the container is now running, and it actually executed the /bin/bash command.

We can go back to where we left by executing docker attach ContainerID command:

k@laptop:~$ docker attach 33b55acb4814

[root@33b55acb4814 /]#

Now, we’re back. To make sure, we can check if there is the file we created:

[root@33b55acb4814 /]# cd /home

[root@33b55acb4814 home]# ls

bogo.txt

![VIDEO] Live Stream Best Practices (1/2) | Believe](https://www.believemusic.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/live.jpg)